“Elite-Fitness” claims to be all about functional fitness. The movements you do in “Elite-Fitness” are things you might have to do around your house or in you job. I, for one, have used the lifting skills and strength learned in “Elite-Fitness” several times working occasional construction and tree jobs. I can deadlift heavy stumps, snatch and carry sheets of plywood over my head, and push-jerk dense packs of roof shingles. In times of recreation, I can clean and jerk small people over my head and throw them into pools, I can run circles around my opponents in sports, do handstands in the yard, or squat down to pick something up while someone is sitting on my shoulders.

All this is very practical, very functional. I do it all without lifting shoes. Shouldn’t we train in the gym under similar conditions that we will face in the real world? This has always been my argument against using lifting shoes. But, after doing some research, I have changed my mind, and now espouse their benefits. In short, with lifting shoes you will be able to lift heavier weights at the box, boost your ego, and more-safely build strength.

A Little History

By taking a look at the development of the lifting shoe we will best be able to see their function.

Back, long ago, when most people currently in the world did not yet exist, in 1929, the International Weightlifting Federation reduced the number of lifts in their competitions down to three: the press, the snatch, and the clean and jerk. The press was to showcase raw strength, and the other two were to showcase explosive power.

At first, the lifters just hoisted up the bar to their chests without going into a deep squat, sort of like a power-clean. Then they started to figure out that if they dropped under the bar as it came up, they didn’t need to lift the bar as high, so they could lift heavier weights. They started doing something between a half-squat and a split, called a “splot”.

Next, they realized that they could go even lower with a standard, straight split, like we often do for medium weights in “Elite-Fitness”. For this, the lifters just used flat soled shoes. Sometimes they used high-topped boxing shoes. The front foot just landed flat, with the shin and thigh of the foreleg being square to one another. Only the ball of the foot and the toes touched the ground on the back foot, until they had caught the weight and then rolled back to the heel.

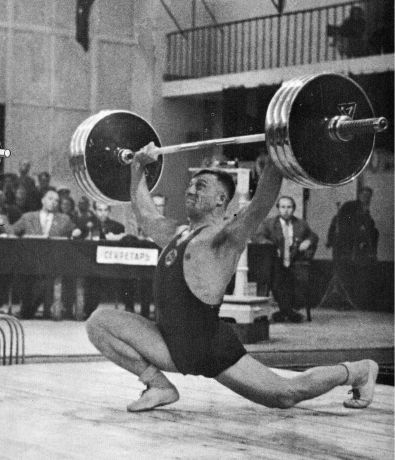

In the quest for catching the bar even lower, some of the lifters, like the Soviet, Rudolf Plukfelder, developed a split that landed with the knee and shin bent forward, acutely over the forefoot. This allowed them to catch more weight, but, due to the limits of ankle flexibility, required the lifter to land on the ball of his forefoot, which compromised balance.

Here’s good old Plukfelder, doing a really deep split. Notice the elevation of his front heel.

That’s when the lifters began to switch from flat shoes to ones with heels. If a lifter wore a work-boot, for instance, he could land on his heel and the ball of his foot simultaneously, providing greater stability, while still bending his knee out forward.

OK

That’s the idea. Since then, they’ve gotten rid of the strict press and we’ve switched from the split to a deep squat, but the high heels of the lifting shoes are still used for the same concept: to allow the knees to bend far out in front of the feet to drop the torso lower.

So, you see, if you want to do really heavy olympic lifts, unless your ankle and Achilles tendon are abnormally flexible, you’ll have to prop up your heels on some lifting shoes.

But it’s not functional, like you said earlier, man!

Yeah, but, if you think about it, our perfectly formed barbells and symmetrical weights aren’t what we encounter in the real world, either, but we train with them because they are safe and build up useful strength. If you train with lifting shoes, you’ll be able to lift more in the gym, which will build up more muscle, faster, so you’ll be stronger without the shoes, too.

What about for other Lifts?

As it turns out, lifting shoes are even useful for lifts that don’t require a deep squat. For example, in research done by Sato et al., lifting shoes were found, when performing back-squats, to help prevent forward-lean, which can really stress and damage the lower back. They also found that lifting shoes possibly engaged the knee extensor muscles more than without, which means they are good for the knees.

If you want to experience the difference, just do two air squats, barefooted: first, with all your weight on your heels; second, with your heels raised an inch, and your weight balancing on the balls of your feet. Aside from the balance issues, you will be able to tell that it’s much easier to keep your back upright.

Of course, you can’t use lifting shoes for box jumps, double-unders, running, etc, because the heels will really get in your way and you’ll probably ruin your shoes. For metcons and non-heavy-lifting, get some flat shoes.

What lifting shoes should I buy?

If you are cheap, or just want to try before you buy, you can wear a pair of work-boots or dress shoes. Just make sure the heel is raised about an inch more than the forefoot. Don’t use any shoes with squishy heels because they will absorb and transfer some of your downward force into horizontal movement, lessening your thrust and possibly rolling your ankle.

If you are ready to buy some real lifting shoes:

Adidas Power Lift Trainer Shoes – $90

Rogue Fitness’s Do-Wins, designed especially for “Elite-Fitness”. $119.

Some Pendley Do-Wins, in some nice colors. ~$119

Adidas AdiPower – $200

I can’t personally recommend any of those, though a trainer at our gym has some Do-Wins and the upper has detached from the heel prematurely. Adidas is supposedly the big name for shoes on the Olympic circuit.

Sources:

Andrew Charniga, Jr. Why Weightlifting Shoes? Sportivny Press.

Sato, Kimitake1; Fortenbaugh, Dave; Hydock, David. “Kinematic Changes Using Weightlifting Shoes on Barbell Back Squat”, Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research: January 2012 – Volume 26 – Issue 1 – pp 28-33

weight lifting is good

is hard work